STEAM Bin Project is a Win-Win for RWU Education Majors and Elementary School Classrooms

Education majors create bins with materials designed for teaching Science, Technology, Engineering, The Arts and Mathematics (STEAM) in elementary schools

TIVERTON, R.I. – What happens when you fill colorful bins with popsicle sticks, cotton balls, cups, and other materials, put the bins on wheels, and roll them into a first-grade classroom?

The possibilities are endless, RWU education majors are discovering.

Seniors Abigail Higgins and Megan Barnes and sophomore Jacqueline Lacerra are all earning a certificate from the RWU Department of Education in the quickly growing field of STEAM education. STEAM, which stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts and Mathematics embraces hands-on learning, critical thinking and problem-solving.

Higgins and Barnes, who are in student-teaching placements this semester, and Lacerra, who is taking a course on implementing technology in the classroom, helped create these bins with support from Professor of Education Margaret Thombs. They used knowledge from their coursework, their experiences in the classroom and their own interests, to put together the bins.

“When I was creating them, I was like ‘this is something I would have liked when I was younger,’” said Lacerra, who has been observing in an elementary school classroom and will soon teach her first lesson using the materials.

The bins are filled with simple props that allow for flexibility and promote student engagement. Along with being used by RWU education majors, they will be left in the classroom for teachers to use as they see fit. Projects can be left open-ended, for students to use their imagination, or they can be incorporated into more structured lessons.

.png)

“They’re very visually appealing and colorful so whenever the cart comes into the room they know it’s going to be something fun,” said Higgins. “You want to have that at the beginning of the lesson, because then you know they’re going to be engaged.”

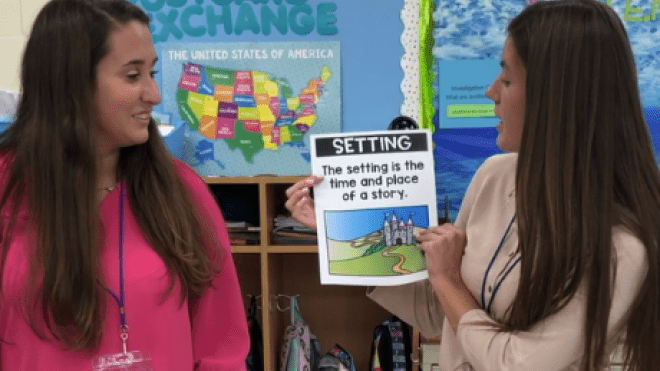

Higgins and Barnes tried out the bins with first graders at the Pocasset Elementary school last month. The activity they ran focused on literacy, art and technology. The first graders chose cards from the bin, with images of different characters, settings and plot ideas to get them started. From there, they created their own stories, either writing the stories down or drawing them. Afterwards, the students recorded each other telling the stories on video.

“For some kids, it was just an overall fun experience, but for others it was necessary because they are visual learners. This made the lesson so much more appealing for them because they felt included,” said Higgins.

Higgins and Barnes were able to see the way students with different learning styles can benefit from STEAM activities.

“STEAM encompasses so many subjects. Every student has the opportunity to shine and do their best with the given content,” said Barnes.

.png)

While creating and implementing the bins in the classroom is a wonderful learning experience for education majors, having the bins on hand is incredibly helpful for young students and their teachers.

“The children and their teachers are excited, because many of the teachers want to implement such things but don’t really have time to put together all the materials,” said Thombs, “So I think it’s a win-win situation for everybody—for our students, for the teachers, for the children in the schools.”

Giving children access to STEAM education at an early age is setting them up for success, not just because of the important skills they will gain, but also because of the career opportunities it can open for them in the future. This is especially true for students with identities that are underrepresented in the field.

“We've learned that certain people, such as young girls, are left out," said Higgins. "They are made to think that there’s not much for them in STEAM when they get older. So putting the idea of STEAM into their minds and getting them engaged with the idea from a young age opens up more doors for them in the future."

Having this experience in teaching STEAM and earning a certification in the field also broadens career opportunities for RWU education majors.

“STEAM is becoming such a big initiative in schools, so if I have the certification, I will be able to match the needs of the students in the classroom,” said Higgins.