Making the Most of Your Research: Advice from Historical Authors

From immersing oneself in timely customs to the pain of parting with a compelling anecdote, historical writers detail their research and writing methods

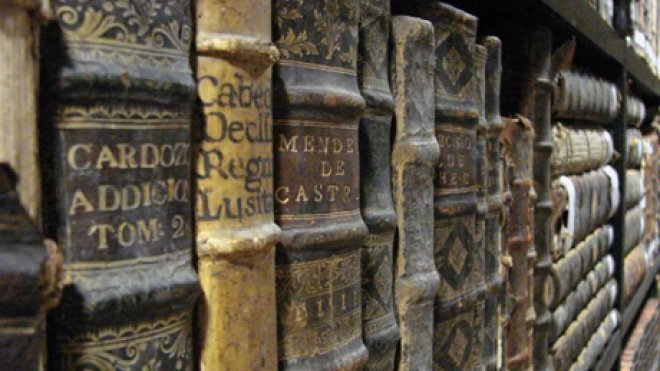

BRISTOL, R.I. – A term that evokes images of long hours spent in the library poring over stacks of textbooks, “research” was branded with a new reputation as “exciting” by two steadfast history buffs in “From the Stacks to the Pages: How Research Tells the Stories from History,” the semester’s final lecture in the Mary Tefft White Cultural Center’s Talking in the Library Series. True to their passions, historical writers Taylor Polites and Jeffrey Meriwether – associate professor of history and Revolutionary War re-enactor – conjured the many roads down which their research has taken them in a lively discussion complete with a bag of props: Royal Navy caps, an HMS Ocean ribbon, and the uniform of a master corporal in the French infantry.

With many aspiring writers among the audience, the speakers opened the conversation by introducing how and where they start their research. For Meriwether, his development of in-depth researching skills began as an undergraduate student who exhausted secondary sources available at the library, compelling him to seek out primary sources. This quest eventually brought him overseas to delve through the United Kingdom’s National Archives, and complemented his acquired knowledge by visiting history museums and talking to descendants of historical figures.

“The more you learn to think critically, the more you start to recognize where to find the best research,” says Meriwether, whose love of history influenced his decision to join the U.S. Navy Reserve and become a Revolutionary War re-enactor with His Majesty’s Tenth Regiment of Foot.

Although his genre is fiction, Polites grounds his writing in research. Already equipped with a fascination of how people encounter the world around them, he began cultivating an appreciation for research as an undergrad student when he set out to approach new avenues in his writing. Author of The Rebel Wife (2012), Polites uses various firsthand accounts from diaries and letters to “piece together the world” his characters lived in. To gain “a glimmer of what life was like in a particular time and place,” he recommends going to the theatre, listening to music, and engaging in customs of the researched time-period. Polites credited AS220, a non-profit community arts center in Providence, for inspiring one of his stories when he took a class on ambrotype, a process that prints photographs onto glass and is viewed through reflected light.

Noting that researchers come across information so fascinating that they can’t bear to part with a compelling anecdote, Adam Braver – panel moderator and the University Library’s writer-in-residence – asked the authors what they do when it doesn’t seem to fit in their writing.

When researching Rhode Islanders and the Spanish-American War, Meriwether discovered a Providence Journal article about local troops stationed down south who would be denied a traditional American Thanksgiving because the soldier responsible for cooking their turkey dinner was imprisoned. Meriwether was fascinated by the newspaper’s daily coverage of the soldier’s imprisonment and demands for his release so the Rhode Island troops wouldn't miss their holiday. After trying to make the quirky anecdote fit, Meriwether decided that forcing it into his narrative wouldn’t help him accomplish his goals for the piece.

“I put it in a footnote and I reference it heavily in the text,” he added with a chuckle.

Polites has faced similar experiences in his writing and learned that fiction writing requires the same focus and discipline as academic writing. He explained that anecdotes can help writers create a world that is interesting and accessible to readers, but he is often surprised at how contemporary and relatable certain historical accounts can seem.

While they pen different writing styles, both writers agree that research is fundamental to informing their stories and directing their writing process. Polites said he knows it’s time to dive back into research and collect more details when he starts to lose interest or momentum while writing. “As I write,” he explained, “this relationship between the research and the writing continues in a very synergistic way.”

Meriwether’s goal is to conduct enough research to establish context and “create an infrastructure you can hang everything on.” But even after gathering sufficient facts to confidently recreate a world, he asserted that writers never know what they might find that influences their perspective in an unexpected way.

“Often it is quite serendipitous, you just happen upon something,” Meriwether said. “You can’t go looking for the turkey dinner stories – they just pop up.”